Telecom network infrastructure powers every internet search, video call, and cloud application you use daily. This interconnected system of fiber-optic cables, wireless antennas, routers, and data centers delivers voice, data, and internet services across the globe. Without it, businesses can’t operate, emergency services can’t respond, and digital commerce grinds to a halt.

I’ve spent 10+ years designing and managing these networks as a CCIE-certified network engineer. I’ve watched infrastructure evolve from copper telephone lines to software-defined, cloud-native architectures supporting 5G networks and billions of IoT devices. The transformation has been remarkable—but also increasingly complex.

This guide breaks down telecom network infrastructure into three essential layers: physical transmission media (fiber, wireless, copper), network architecture components (routers, switches, protocols), and management systems (monitoring, orchestration, analytics). You’ll understand how these pieces work together to deliver reliable connectivity, why 5G requires denser deployments than 4G, and how virtualization is replacing expensive hardware appliances with flexible software.

Whether you’re a network engineer pursuing CCIE certification, an IT professional managing enterprise networks, or a technology enthusiast seeking to understand modern connectivity, this guide provides practical knowledge you can apply immediately. I’ll cover everything from fiber optic transmission principles to emerging technologies like Open RAN and edge computing—without the marketing fluff or unnecessary jargon.

Key Takeaways

-

Telecom infrastructure comprises three core elements: physical transmission media (fiber, wireless), network equipment (routers, switches), and operational platforms (data centers, management systems)

-

5G networks require significantly denser small cell deployments, cloud-based radio access network architectures, and 10-100x higher backhaul capacity compared to 4G

-

Network Functions Virtualization (NFV) and Software-Defined Networking (SDN) are replacing hardware appliances with software running on standard servers, reducing costs and improving deployment speed

-

Edge computing infrastructure positions processing resources closer to users, enabling ultra-low latency applications like autonomous vehicles and industrial automation

-

Modern infrastructure management relies on streaming telemetry, digital twins, and predictive analytics rather than traditional monitoring approaches

What Is Telecom Network Infrastructure?

Telecom network infrastructure encompasses the interconnected physical and digital systems that deliver telecommunications services globally. I define it in three fundamental categories: transmission media carrying signals, network equipment routing traffic, and operational platforms managing network functions.

The transmission layer includes fiber optic cables forming backbone networks, wireless systems providing mobile connectivity, and legacy copper lines still serving some last-mile connections. Network equipment comprises routers making intelligent forwarding decisions, switches handling high-speed local traffic, and base stations connecting wireless devices. Operational platforms include data centers housing critical servers, network operations centers monitoring performance 24/7, and cloud platforms running virtualized network functions.

Modern telecom infrastructure has evolved dramatically from Time Division Multiplexing (TDM) circuits and copper wiring to Internet Protocol (IP)-based, virtualized architectures. Today’s networks span from local access systems connecting individual homes and businesses to global backbone infrastructure carrying terabits of traffic between continents.

This infrastructure supports essential services businesses and individuals depend on daily:

-

Email and voice communications

-

Cloud-based software applications

-

Remote work capabilities

-

Streaming entertainment

-

Point-of-sale systems and payment processing

-

Cybersecurity operations

-

Emergency 911 services

Without reliable network infrastructure, none of these functions operate effectively.

Governments classify telecom infrastructure as critical national and economic assets requiring continuous investment. The proliferation of 5G networks, IoT devices, and artificial intelligence applications has only intensified infrastructure’s importance. Network capacity demands double every 18-24 months in many markets, driving ongoing upgrades and expansion.

I’ve designed networks for major internet service providers where outages lasting minutes cost millions in revenue and customer trust. That economic reality underscores why infrastructure reliability, capacity, and performance aren’t optional—they’re fundamental to modern society’s functioning.

Core Physical Infrastructure Components

Physical infrastructure forms the foundation transporting telecommunications traffic between locations. Understanding these tangible elements is essential for anyone working with modern networks.

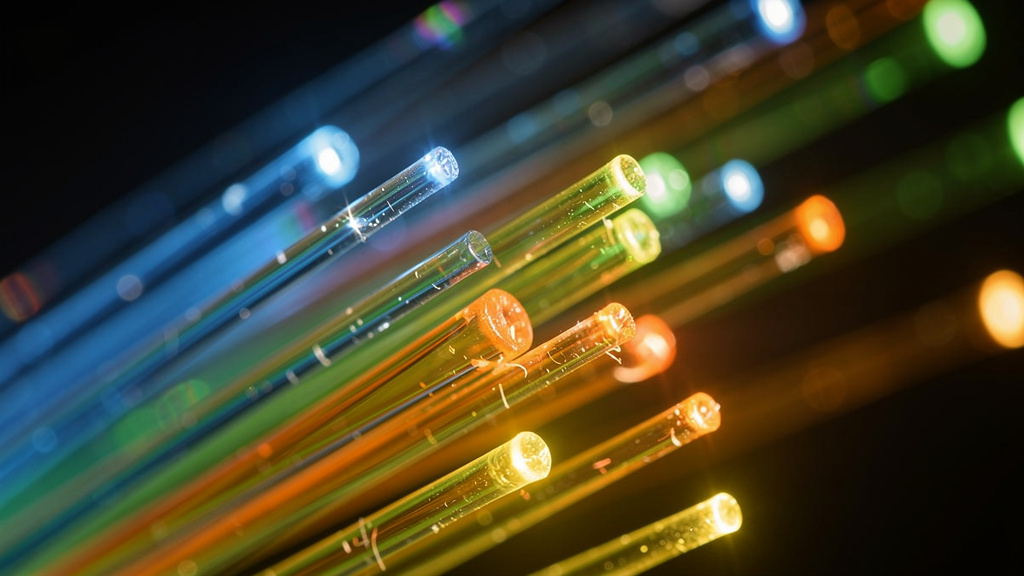

Fiber Optic Cable Systems

Fiber optic technology transmits data as light pulses through ultra-thin glass or plastic fibers. I’ve deployed fiber networks where single strands carry 100 Gbps, 400 Gbps, or even terabit transmission rates—bandwidth impossible with copper media.

Fiber’s dominance stems from several technical advantages. Light signals travel dozens of kilometers without degradation requiring amplification. Electromagnetic interference from power lines or radio sources doesn’t affect optical transmission. Single fiber strands support wavelength division multiplexing (WDM), transmitting multiple independent signals on different light wavelengths simultaneously.

Network deployments use two primary fiber types:

-

Single-mode fiber with extremely narrow core diameter (8-10 microns) supports long-distance transmission spanning hundreds of kilometers—ideal for backbone networks connecting cities

-

Multimode fiber with wider cores (50-62.5 microns) handles shorter runs up to 2 kilometers, commonly deployed in data centers and campus environments

I’ve participated in infrastructure projects replacing copper with fiber across metro networks. Service providers prioritize fiber deployment because it future-proofs networks against capacity growth for decades. Once buried or aerial fiber is installed, upgrading transmission speeds often requires only replacing endpoint equipment, not the fiber itself.

“Fiber optic infrastructure represents the most significant long-term investment in telecommunications, providing bandwidth scalability that will serve network demands for the next 20-30 years.” — Industry Network Architect

Wireless Infrastructure Elements

Wireless infrastructure uses electromagnetic radio waves to deliver connectivity without physical cables. Cell towers and macro sites form the backbone of mobile networks, with large tower structures supporting multiple antennas providing wide-area coverage across several kilometers.

Small cells have become critical for modern networks, particularly 5G deployments. These compact, low-power nodes attach to street furniture, building facades, or utility poles, adding capacity and coverage in dense urban environments. Where traditional macro towers might serve areas measured in square kilometers, small cells cover only hundreds of meters—but in my experience, they’re essential for meeting 5G’s performance targets in cities.

Distributed Antenna Systems (DAS) solve challenging RF environments. Large stadiums, airport terminals, and commercial high-rises often have poor cellular coverage due to building construction. DAS networks distribute multiple antennas throughout these structures, all connected to centralized radio equipment, providing consistent indoor coverage.

Rooftop installations provide another deployment option, mounting wireless equipment on buildings rather than constructing new towers. This approach reduces infrastructure costs and deployment timelines, though coverage patterns differ from traditional tower sites.

Satellite infrastructure extends connectivity to remote areas where terrestrial deployment is impractical. Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite constellations increasingly supplement traditional ground-based networks, though latency and capacity constraints limit satellite’s role compared to terrestrial fiber and wireless systems.

Legacy and Hybrid Media

Copper twisted-pair cabling once dominated telecommunications, carrying analog voice circuits and early Digital Subscriber Line (DSL) internet services. I’ve worked with service providers systematically decommissioning copper infrastructure, migrating customers to fiber-based services. Copper remains in legacy deployments, but most markets have established sunset timelines for these aging systems.

Coaxial cable serves cable television operators delivering broadband internet via DOCSIS technology. Modern DOCSIS 3.1 and upcoming DOCSIS 4.0 standards support multi-gigabit speeds over coax, extending the medium’s viability despite fiber’s technical superiority.

Hybrid Fiber-Coaxial (HFC) networks combine fiber optic backbone infrastructure with coaxial distribution to individual premises. Cable operators use HFC as a migration path—extending fiber deeper into neighborhoods over time while using existing coax for the final connection. This staged approach balances infrastructure investment against service capabilities.

Network Architecture Layers and Functions

Telecom networks organize into distinct functional layers, each handling specific responsibilities in delivering end-to-end connectivity.

Physical Layer Components

The physical layer comprises hardware elements managing actual signal transmission. Routers make intelligent forwarding decisions, examining packet destination addresses and consulting routing tables to determine optimal paths through the network. In my data center designs, core routers handling 400 Gbps interfaces route traffic between thousands of network segments.

Switches operate at Layer 2, forwarding traffic within local networks using MAC address tables rather than IP routing. High-performance switches in carrier networks support terabits of aggregate switching capacity, connecting hundreds of servers or network devices.

Network interface cards (NICs) provide endpoint connectivity, converting between digital data and electrical or optical signals for transmission. Modern 100 Gbps NICs in servers demonstrate how interface speeds have scaled with network capacity demands.

Physical cabling infrastructure—structured wiring systems, fiber distribution frames, patch panels—may seem mundane, but I’ve seen network outages traced to damaged cables or improper terminations. Physical layer integrity directly impacts everything running above it.

Transport and Protocol Layers

Transport protocols manage reliable data delivery across networks. Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) provides connection-oriented communication with error detection, retransmission, and flow control—essential for applications requiring guaranteed delivery like file transfers and web browsing.

User Datagram Protocol (UDP) offers connectionless transmission without TCP’s overhead, suitable for time-sensitive applications tolerating occasional packet loss like voice calls and video streaming.

Routing protocols enable dynamic network topology learning and traffic engineering:

-

Open Shortest Path First (OSPF) calculates optimal paths within autonomous systems using link-state advertisements. I frequently adjust OSPF cost metrics to influence traffic patterns, steering bandwidth-intensive flows across preferred high-capacity links

-

Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) interconnects different autonomous systems, forming the Internet’s routing foundation. BGP’s path selection mechanisms using AS-path length, local preference, and other attributes enable sophisticated traffic engineering between service providers

Multiprotocol Label Switching (MPLS) improves forwarding efficiency by using labels rather than full IP address lookups. MPLS also enables traffic engineering and Virtual Private Network (VPN) services, making it popular in service provider networks.

Quality of Service (QoS) mechanisms prioritize delay-sensitive traffic like voice and video over less time-critical data transfers, providing consistent application performance during congestion.

Application and Services Layer

Application layer protocols enable user-facing services running on transport infrastructure. HTTP and HTTPS carry web traffic and API communications forming the basis of modern cloud applications. Domain Name System (DNS) translates human-readable domain names into IP addresses—a critical service I ensure has redundancy and security protections in every network design.

Email protocols including Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) for sending messages and Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP) or Post Office Protocol (POP3) for retrieval remain fundamental despite messaging platforms’ popularity.

Voice over IP (VoIP) signaling protocols like Session Initiation Protocol (SIP) and H.323 establish and manage real-time communication sessions. These protocols work with Real-time Transport Protocol (RTP) carrying actual voice and video streams.

Management and Orchestration Layer

Network management platforms provide configuration, monitoring, and troubleshooting capabilities across distributed infrastructure. Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP) has traditionally enabled device monitoring and data collection, though limitations in scalability and granularity have driven adoption of newer approaches.

Streaming telemetry using protocols like gNMI (gRPC Network Management Interface) provides high-frequency, model-driven network data collection. I’ve implemented telemetry systems providing per-second interface statistics and routing protocol state updates—visibility impossible with SNMP’s polling-based architecture.

Orchestration systems automate service provisioning and lifecycle management. Rather than manually configuring individual devices, orchestrators translate service definitions into device-specific configurations, deploy them across infrastructure, and continuously verify intended state.

Analytics platforms process network data to enable capacity planning, performance optimization, and anomaly detection. Machine learning models analyzing telemetry streams can predict failures and trigger automated remediation before service impacts occur.

Data Centers and Backbone Infrastructure

Data centers house the servers, storage systems, and network equipment processing telecommunications traffic at scale. I’ve designed carrier-grade data centers where redundancy and resilience are paramount—dual power feeds from separate substations, N+1 cooling systems, geographically distributed facilities enabling disaster recovery.

Core network equipment in these facilities includes high-capacity routers and switches forming network backbones. These systems aggregate traffic from thousands of access networks, handling routing table sizes with millions of prefixes and forwarding decisions at terabit speeds. Single device failures can’t impact service, so designs incorporate redundant hardware, diverse fiber paths, and automated failover protocols.

Colocation facilities provide neutral interconnection points where multiple carriers exchange traffic. Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) in major metros enable direct peering between networks, improving performance and reducing transit costs. As a network designer, I prioritize establishing presence in key colocation facilities to optimize connectivity.

Network Operations Centers (NOCs) provide 24/7 monitoring and incident response. NOC staff track performance metrics, respond to alerts, coordinate maintenance windows, and manage configuration changes. Modern NOCs increasingly rely on automation and artificial intelligence to handle routine tasks, allowing engineers to focus on complex troubleshooting and strategic projects.

Edge computing infrastructure brings processing resources closer to end users, reducing latency for time-sensitive applications. Multi-Access Edge Computing (MEC) facilities at cell tower sites or central offices enable sub-10 millisecond response times impossible when traffic must traverse to distant centralized data centers.

Energy efficiency has become critical in data center design. Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) metrics comparing total facility power to IT equipment power drive cooling optimization and renewable energy integration. I’ve worked with operators targeting PUE ratios below 1.2, meaning minimal power waste on cooling and supporting infrastructure.

5G Network Infrastructure Requirements

Fifth-generation wireless networks impose demanding infrastructure requirements far exceeding 4G LTE capabilities. I’ve participated in 5G planning where performance targets seemed audacious—10 Gbps peak speeds, sub-1 millisecond latency, and supporting 1 million devices per square kilometer.

Network slicing technology enables creating multiple virtual networks with different performance characteristics on shared physical infrastructure. An operator might simultaneously support:

-

Enhanced mobile broadband slices for consumer smartphones

-

Ultra-reliable low-latency slices for industrial automation

-

Massive IoT slices for sensor networks

All using common radio and core infrastructure but with isolated, guaranteed resources.

Cloud RAN architecture centralizes and virtualizes Radio Access Network functions previously requiring dedicated hardware at every cell site. Instead of baseband processing units at each tower, Cloud RAN platforms in edge data centers serve multiple radio sites, improving resource utilization and enabling features like coordinated multipoint transmission across cell boundaries.

Massive MIMO (Multiple Input Multiple Output) antenna arrays with 64 or more elements enable spatial multiplexing and beamforming. I’ve seen 5G base stations using massive MIMO simultaneously communicate with dozens of devices on the same frequency by precisely directing signals in space—dramatically improving spectral efficiency versus 4G’s simpler antenna designs.

Millimeter wave spectrum between 24-100 GHz provides enormous bandwidth supporting multi-gigabit speeds. However, these high frequencies suffer severe propagation limitations—signals barely penetrate buildings and cover only hundreds of meters. This physical reality drives 5G’s requirement for dense small cell deployments in urban areas.

Backhaul infrastructure upgrades represent massive investment. Where 4G cell sites might use 1 Gbps fiber connections, 5G sites require 10 Gbps or higher capacity to handle radio network throughput increases. Operators face difficult economics deploying fiber to thousands of additional small cell locations.

“5G infrastructure deployment costs approximately 3-5 times more per site than 4G due to density requirements, backhaul upgrades, and advanced antenna systems.” — Telecommunications Industry Report

Power infrastructure presents another challenge. 5G equipment consumes significantly more electricity than 4G. I’ve designed cell site power systems providing adequate electrical service, backup batteries, and potentially backup generators for critical locations.

Phased migration strategies balance 5G’s benefits against deployment costs. Non-standalone (NSA) 5G initially uses existing 4G core networks, allowing radio upgrades without complete core replacement. Standalone (SA) 5G builds complete end-to-end 5G architecture—higher cost but enabling full feature set including network slicing.

Network Virtualization and Software-Defined Infrastructure

The telecommunications industry is undergoing fundamental transformation from purpose-built hardware to software-defined architectures. This shift impacts infrastructure deployment, operations, and economics.

Network Functions Virtualization (NFV)

NFV runs network services as software on standard x86 servers rather than dedicated appliances. I’ve overseen NFV migrations where operators replaced racks of proprietary firewalls, load balancers, and deep packet inspection systems with virtual network functions (VNFs) running on commodity servers.

Virtualized functions span routing, firewall services, session border controllers managing VoIP traffic, evolved packet core (EPC) elements for 4G networks, and 5G core network functions. Each VNF operates as software, typically packaged as virtual machine images deployed on NFV Infrastructure (NFVI)—the compute, storage, and networking resources hosting VNFs.

Business benefits are compelling:

-

Hardware costs decrease when generic servers replace specialized appliances

-

Service deployment accelerates from months to days when spinning up VNFs versus ordering, racking, and configuring physical equipment

-

Scalability improves by adding compute resources rather than forklift hardware replacements

However, NFV introduces operational challenges. Performance sometimes lags purpose-built hardware, particularly for intensive packet processing workloads. Orchestration complexity increases when managing hundreds of VNF instances across distributed infrastructure. Vendor ecosystems are still maturing with interoperability gaps between different implementations.

I’ve seen successful NFV deployments in mobile core networks where operators virtualized EPC and 5G core functions. Enterprise CPE (Customer Premises Equipment) also virtualizes well—universal CPE platforms running VNF-based routing, firewalls, and SD-WAN services.

Software-Defined Networking (SDN)

SDN decouples network control planes making routing decisions from data planes forwarding packets. Centralized SDN controllers manage distributed switching and routing elements through southbound APIs including OpenFlow, NETCONF, and RESTCONF.

Traditional networks require configuring each device individually. SDN centralizes policy definition and configuration, with controllers pushing device-specific instructions. This architectural shift enables network programmability—applications using northbound APIs can dynamically adjust network behavior without manual device configuration.

I’ve implemented SDN for dynamic traffic engineering, automatically adjusting routing based on real-time congestion and link utilization. When monitoring detects congestion on primary paths, SDN controllers reroute affected traffic to alternative paths within seconds—faster than any manual intervention.

SD-WAN applies SDN principles to wide area networking, particularly for enterprise connectivity. SD-WAN platforms intelligently route traffic across multiple connection types (MPLS, broadband internet, LTE) based on application requirements and real-time performance. I’ve helped businesses reduce WAN costs 40-50% by replacing expensive MPLS circuits with broadband connections managed by SD-WAN intelligence.

Implementation models vary:

-

Overlay SDN operates at the application layer, creating virtual networks above existing physical infrastructure

-

Underlay SDN directly controls physical network devices, offering more comprehensive capabilities but requiring compatible hardware

Cloud-Native Networking

Cloud-native networking represents NFV’s evolution using containerized workloads and microservices architectures. Rather than monolithic VNF applications packaged as virtual machines, network functions decompose into independent microservices running in containers—commonly using Kubernetes orchestration.

Container-based implementations start faster, scale more efficiently, and consume fewer resources than VM-based VNFs. A containerized routing function might consist of separate microservices for BGP processing, route calculation, and forwarding table management—each scaling independently based on demand.

DevOps integration brings continuous integration/continuous deployment (CI/CD) pipelines to network function development. Code commits trigger automated testing and deployment, accelerating innovation cycles from months to weeks or days.

I’ve observed cloud-native networking improving operational efficiency versus traditional VNF approaches. However, adoption remains early stage with vendors still developing production-grade implementations for carrier-grade network functions.

Enterprise and Private Network Infrastructure

Enterprises increasingly deploy dedicated network infrastructure rather than relying solely on public carrier services. Private LTE and 5G networks use licensed, unlicensed (Citizens Broadband Radio Service in the US), or shared spectrum to provide enterprise-controlled cellular connectivity.

Manufacturing facilities deploy private 5G supporting industrial automation—connecting robots, sensors, and control systems with deterministic latency and reliability impossible on public networks. Warehouse logistics operations use private LTE connecting mobile scanners and automated guided vehicles across large facilities. University campuses establish private networks delivering consistent coverage and capacity for student and faculty users.

Spectrum options determine private network feasibility:

|

Spectrum Type |

Characteristics |

Best For |

|---|---|---|

|

Licensed |

Exclusive rights, high cost |

Large enterprises, critical operations |

|

CBRS (US) |

Shared 3.5 GHz band |

Medium deployments, cost-conscious projects |

|

Unlicensed |

Global availability, interference risk |

Small-scale, non-critical applications |

Architecture models vary. Standalone private networks feature dedicated core infrastructure on enterprise premises with complete operator control. Hybrid approaches integrate private radio access networks with carrier roaming for coverage beyond private network boundaries. Edge computing commonly integrates with private networks, placing application logic and data processing directly on enterprise infrastructure.

SD-WAN infrastructure has transformed enterprise wide area networking. Where businesses historically purchased expensive MPLS circuits for guaranteed performance, SD-WAN platforms enable intelligent routing across commodity broadband connections. Application-aware routing directs latency-sensitive traffic like VoIP and video conferencing to optimal paths while offloading bulk data transfers to cheaper, higher-latency connections.

I’ve designed SD-WAN deployments reducing enterprise WAN costs significantly while improving application performance through intelligent path selection and local internet breakout rather than backhauling all traffic to centralized data centers.

Neutral host deployments provide shared wireless infrastructure serving multiple operators in stadiums, airports, and commercial buildings. Rather than each carrier deploying separate small cells and DAS, neutral hosts build common infrastructure that multiple carriers use—reducing deployment costs and improving time-to-coverage. This model is expanding as 5G densification requirements make individual carrier deployments economically challenging.

Infrastructure Management Best Practices

Managing modern telecom infrastructure requires disciplined methodologies providing reliability and performance.

Data-driven network planning uses coverage maps, signal strength measurements, and traffic analytics guiding infrastructure investment decisions. I analyze heat maps showing user density and traffic volume identifying where capacity upgrades or additional cell sites deliver maximum impact. This analytical approach provides capital efficiency—building infrastructure where demand justifies investment.

Performance monitoring through continuous KPI collection provides visibility into network health. Metrics including throughput, latency, packet loss, and jitter tracked across all infrastructure segments enable rapid issue detection. When monitoring alerts on degraded performance, engineers investigate and remediate before customer impacts occur.

Predictive analytics applies machine learning to network data for proactive management. Models analyzing historical patterns predict capacity exhaustion, enabling preemptive upgrades. Anomaly detection algorithms identify unusual network behavior potentially indicating developing problems. I’ve implemented systems generating maintenance tickets automatically when predictions indicate high failure probability within 30 days.

Remote inspection technologies including drones and sensors capture field-verified infrastructure data without expensive site visits. Drone inspections of cell towers document antenna orientation, equipment installation, and physical condition. Sensor-based monitoring tracks equipment temperature, power consumption, and other parameters indicating potential issues.

Digital twin implementations create virtual infrastructure replicas comparing as-designed versus as-built states. When deployment teams install equipment, as-built data populates digital twins enabling validation against design specifications. Discrepancies flag configuration errors or unauthorized changes requiring attention.

Configuration management including version control, automated backups, and change tracking prevents configuration drift. I maintain network device configurations in Git repositories with peer review for changes and rollback capability when updates cause issues.

Capacity planning discipline requires analyzing traffic growth trends, monitoring headroom, and proactively expanding before saturation. Waiting until circuits reach 100% utilization before upgrades risks service degradation. Best practice targets 50-70% utilization thresholds triggering expansion projects.

Emerging Technologies and Future Trends

Several transformative technologies are reshaping telecommunications infrastructure’s future direction.

Open RAN promotes disaggregated, multi-vendor radio access network architectures using open interfaces standardized by organizations like O-RAN Alliance. Traditional RAN deployments use integrated systems from single vendors. Open RAN separates radio units, distributed units, and centralized units from different vendors interoperating through standardized interfaces.

Benefits include vendor diversity reducing lock-in, potentially lower costs through increased competition, and accelerated innovation as more participants contribute. However, interoperability complexity, performance validation, and ecosystem maturity present adoption challenges. I’ve evaluated Open RAN for large-scale deployments—the technology shows promise but requires careful planning and testing.

Multi-Access Edge Computing positions computing resources at network edge locations like cell tower sites and central offices. MEC enables ultra-low latency applications including augmented reality, autonomous vehicles, and industrial automation requiring response times under 10 milliseconds impossible when processing occurs in distant centralized data centers.

I’ve worked with operators deploying MEC infrastructure supporting autonomous vehicle testing where vehicle control decisions can’t tolerate latency from cloud processing. Edge computing also reduces backhaul traffic by processing data locally rather than transporting it to centralized facilities.

6G research initiatives are targeting next-generation wireless capabilities—peak speeds exceeding 100 Gbps, sub-millisecond latency, AI-native architecture, and sensing capabilities beyond just communication. Commercial deployment isn’t expected before 2030, but research now shapes standards and technology development.

Satellite-terrestrial integration combines Low Earth Orbit satellite constellations like Starlink and OneWeb with ground-based networks. Satellites extend coverage to unserved remote areas while terrestrial infrastructure handles capacity in populated regions. This hybrid approach addresses connectivity gaps economically infeasible for terrestrial-only deployment.

WiFi 6E and emerging WiFi 7 use 6 GHz spectrum (in markets where regulators have authorized it) delivering multi-gigabit wireless speeds. These technologies increasingly compete with cellular for fixed wireless access and dense indoor connectivity applications.

Convergence trends unify previously separate network domains:

-

Fixed-mobile convergence combines wireline and wireless services on common infrastructure

-

IP and optical convergence integrates routing and optical transport capabilities in single platforms reducing network layers

I’m designing architectures treating wireline, wireless, and data center networks as unified infrastructure rather than independent silos.

“The future of telecommunications infrastructure lies not in isolated technology silos, but in converged, software-defined platforms that adapt dynamically to changing demands.” — Network Infrastructure Strategist

From my perspective analyzing emerging technologies, infrastructure will increasingly emphasize software-defined, cloud-native, and open architectures reducing vendor dependency while improving operational flexibility and efficiency.

Conclusion

Telecom network infrastructure forms modern society’s communication foundation—enabling business operations, emergency services, digital commerce, and social connectivity we often take for granted. I’ve broken down this complex system into three essential pillars: physical transmission media carrying signals, network architecture layers managing traffic, and operational systems providing reliable performance.

Infrastructure has shifted from purpose-built hardware appliances to software-defined, virtualized platforms running on commodity servers and cloud infrastructure. 5G wireless deployments accelerate this shift, requiring cloud-based radio access networks, dense small cell deployments, and massive backhaul capacity increases versus previous cellular generations.

Understanding these fundamentals equips network professionals to design resilient systems, troubleshoot complex issues, and architect approaches meeting evolving requirements. The industry continues rapid evolution—Network Functions Virtualization, Software-Defined Networking, Open RAN, and edge computing represent significant departures from traditional approaches.

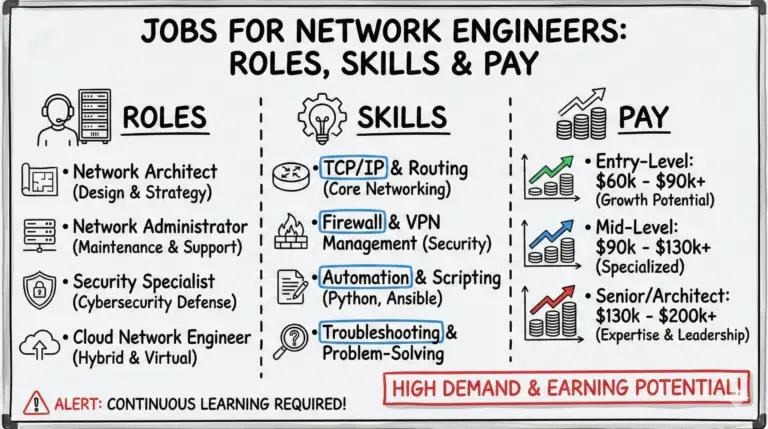

For those pursuing network engineering careers, I recommend:

-

Hands-on laboratory experience with routing, switching, and wireless technologies

-

Vendor certifications including Cisco’s CCIE

-

Cloud platform expertise (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud)

-

Participation in open-source networking communities

Infrastructure investment remains critical for economic competitiveness, digital inclusion, and technological innovation. As networks support artificial intelligence workloads, autonomous systems, and yet-unimagined applications, infrastructure capacity and capability requirements will only intensify.

From my 17 years designing these networks, one constant persists: infrastructure demands continuous learning. Technologies evolving today will soon be legacy systems replaced by innovations currently in laboratories. Stay curious, keep learning, and remember that behind every app, video call, and web page stands sophisticated infrastructure making it all possible.

FAQs

What Are the Three Main Types of Telecom Infrastructure?

Telecom infrastructure divides into three fundamental categories working together to deliver end-to-end services. Physical transmission media including fiber optic cables, wireless radio systems, and copper lines carry signals between locations. Network equipment comprising routers, switches, cell towers, and base stations routes and forwards traffic across networks. Operational platforms including data centers, network operations centers, management systems, and cloud infrastructure enable network control, monitoring, and service delivery. These three layers interdependently provide the capabilities businesses and consumers rely on for connectivity.

What Is the Difference Between 4G and 5G Infrastructure?

5G infrastructure differs fundamentally from 4G in architecture and deployment density. 5G requires significantly more small cell sites per square kilometer versus 4G’s macro cell tower focus—often 3-5x the radio sites in urban areas. Cloud RAN virtualizes baseband processing functions on centralized servers rather than dedicated hardware at each cell location. Backhaul fiber capacity must increase 10-100x to support 5G radio network throughput. 5G core networks feature cloud-native, microservices-based architectures enabling network slicing—creating multiple virtual networks with different performance characteristics on shared infrastructure. Millimeter wave spectrum utilized by 5G requires dense deployments due to limited propagation range versus 4G’s lower frequencies.

How Does Fiber Optic Infrastructure Work?

Fiber optic technology transmits data as pulses of light through ultra-thin glass or plastic fibers using the principle of total internal reflection. Laser or LED light sources at transmit endpoints encode data as rapid on/off light pulses. Light travels through the fiber core, continuously reflecting off the cladding boundary without escaping. Single-mode fiber with 8-10 micron core diameter supports long-distance transmission spanning 100+ kilometers using coherent optical technology. Multimode fiber with 50-62.5 micron cores handles shorter distances up to 2 kilometers commonly in data centers. Wavelength Division Multiplexing transmits multiple independent signals simultaneously on different light wavelengths through single fiber strands—enabling terabit aggregate capacity. Minimal signal attenuation and electromagnetic immunity make fiber the dominant transmission medium for modern high-capacity networks.

What Is Network Functions Virtualization (NFV)?

NFV runs network services as software applications on standard x86 servers rather than purpose-built hardware appliances. Examples include virtual routers, firewalls, load balancers, deep packet inspection systems, and session border controllers managing VoIP traffic. These virtualized network functions (VNFs) deploy on NFV Infrastructure (NFVI) providing compute, storage, and networking resources—typically using virtual machine or container technologies. Benefits include lower hardware costs by using commodity servers, faster service deployment spinning up VNFs in minutes versus ordering physical equipment, and improved scalability adding compute resources rather than hardware replacements. Mobile carriers extensively deploy NFV for evolved packet core (4G) and 5G core network functions, reducing infrastructure costs while improving operational agility.

Why Is Edge Computing Important for Telecom Infrastructure?

Edge computing positions processing resources at network edge locations close to end users rather than distant centralized data centers, enabling ultra-low latency applications. Round-trip time to servers hundreds of kilometers away typically exceeds 20-50 milliseconds—too slow for real-time applications like autonomous vehicle control, industrial automation, augmented reality, and interactive gaming requiring sub-10 millisecond response. Multi-Access Edge Computing platforms at cell tower sites and central offices process data locally, dramatically reducing latency. Edge deployment also decreases backhaul traffic and associated bandwidth costs by processing or filtering data before transporting to centralized facilities. For 5G networks supporting ultra-reliable low-latency communications use cases, edge infrastructure is essential enabling new service offerings and revenue opportunities impossible with traditional centralized architectures.

- Telecom Network Infrastructure: Complete Guide to Components & Design - January 6, 2026

- TP-Link TL-SG108E vs Netgear GS308E: Budget Smart Switches - January 5, 2026

- MikroTik CRS305-1G-4S+ Review: The Ultimate Budget SFP+ Switch Guide - December 25, 2025